There they are on the menu – grilled octopus, calamari, squid ink linguine. Is it OK to eat cephalopods? Or are these animals too smart for us to kill and consume them just because they taste good?

I have stopped eating them, especially octopuses. But I think of this as a decision made for sentimental reasons, not for reasons of principle. This is because I still eat various other kinds of meat, though I avoid (imperfectly) the products of cruel factory-farming. The octopuses that end up on menus are short-lived and wild-caught animals, and do not come from endangered species. Anyone who eats bacon or salami is eating an animal that was kept in captivity and killed for food despite having high intelligence and an undeniable capacity to suffer. In the case of factory-farmed pigs living in close confinement, their treatment is terrible and the suffering must be very great. But even with humanely farmed animals, it is hard to see how eating steak could be justifiable while eating octopuses was not. As I still eat steak, I can’t claim that my avoidance of octopuses is based on a principle that is being consistently applied. So I think of it as a largely sentimental choice; I just don’t want to eat them any more.

Now the ethical issue is on the table, though, what kinds of “smartness” are morally relevant? Which features of an animal’s intelligence and lifestyle are the ones that matter to a decision like this?

The capacity to suffer is an obviously relevant feature, one that philosophers like Peter Singer have focused attention on for many years. For a while discussions in this area were often based on a common-sense picture of which behaviors indicate a capacity to feel pain. Two lines of work are presently going deeper. First, there is impressive physiological work on which animals feel pain. Other work tries answer these questions: once we agree that physical pain is bad, which features of an animal make it able to experience more complicated forms of suffering, in the way humans can? Which animals can experience fear that goes beyond immediate physical threats? Which ones form relationships, or plans, that magnify the ways in which life can go well or badly for them?

In the case of octopuses we are a long way from giving good answers to most of that second set of questions. The existence of stress can be pretty clear in octopuses, and that is one important form of suffering that goes beyond immediate physical injury. As we learn more about the complicated way they engage with the world, some of these findings may end up being morally relevant. An example of what I called “the complicated way they engage with the world” is the fact that some octopuses recognize and react differently to individual human keepers when they are in captivity. Anecdotes of this kind came out of labs and aquariums for years, often because an octopus took an apparent dislike to a keeper, sometimes the one whose job it was to clean the tank. This keeper would be drenched with water whenever they came nearby. So far this is just anecdote. But in 2010 Roland Anderson and his co-workers tested this more rigorously with an experiment on the Giant Pacific Octopus. To avoid making the task too easy, the different humans working with the octopuses wore the same clothes. The octopuses did, after a few weeks, distinguish pretty clearly between a human who fed and a human who slightly irritated them. (I am not sure from the paper how much individual variation there was – whether all octopuses did this or just some of them.)

The welfare of octopuses in research has become a contentious topic. When I first read some of the classic papers about octopus brains and behavior from the 1970s, I was shocked at how brutal the treatment often was. Things have changed, fortunately. In 1986 the United Kingdom set a level of protection in experiments that was applied to all vertebrate animals plus a single species of octopus, Octopus vulgaris. Then in 2010 the European Union laid down quite strict protections for all cephalopods, because of “scientific evidence of their ability to experience pain, suffering, distress and lasting harm.” I have heard some criticism of this new rule, especially because of the paperwork burden it will create. Although few things drive me madder than administrative paperwork, I am glad to see this step.

Given all this, why don’t I just become a vegetarian?

Perhaps I should, and I admire vegetarians. I have no problem with carnivory in itself, though, or with keeping animals for food. The problems are with how it’s done. Farmed animals can be given a life worth living, ending in a quick and low-stress death. Some animals through the history of domestication and farming have been given a life like this, and others have not. Most current farming is probably far from this standard. It would be better not to live at all than to live as a factory-farmed mammal. In the US, high-density farming of cattle and pigs seems especially bad. In Australia, the “live export” of sheep and cattle in suffocatingly hot container ships to countries in the Middle East and Asia where they are slaughtered in brutal ways is sickening – allowing this, when it could be so easily stopped, is the worst thing the country currently does. I don’t think it would be so difficult to give all farmed animals – animals whose existence we are entirely responsible for – a life worth living. To the extent that we can’t or won’t do this, we should stop bringing those lives into being.

_____________

Notes

A new survey article by Robert Jones about animal welfare and sentience is here. A book about all these issues by someone who knows them much better than I do, Lori Gruen, is here.

A 2008 report on factory farming in the US, by the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, looking at public health and economics as well as animal welfare, is here. From the report: “The present system of producing food animals in the United States is not sustainable and presents an unacceptable level of risk to public health and damage to the environment, as well as unnecessary harm to the animals we raise for food.”

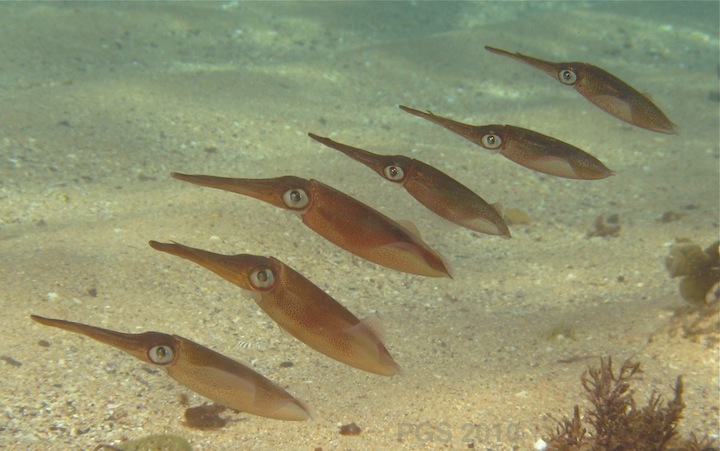

The octopus-plus-camera-lens photo was taken with Matt Lawrence at Octopolis.

Does anyone know what the decorative red swirl is on the second photo above, the one where an octopus is presenting a scallop shell like a shield?

Thank you for this courageous and honest post. It’s really fantastic to see scientists and philosophers publicly acknowledging they stop eating octopuses on the basis on their recognition of their psychological life. I think you should not see this decision as being “made for sentimental reasons, not for reasons of principle”. First, we should not, as feminist philosophers like Lori Gruen has argued for many years, oppose sentiments and principles. Second, when our behaviors do not fit with our moral principles and moral sensibilities, the solution is not to deny those principles, but try to change our behaviors and habits. You seem ready to do this when you acknowledge the atrocities of factory farming and live export.

From what I understand, you are hesitant to stop eating meat on the basis of the “theoretical possibility” that domesticated animals could be bred and killed without too much suffering. Whether this is true or not (I don’t think it is) is not decisive because this ideal world is far from our reality. We now kill 56 billion land animals per year and the UN predicts this will double by 2050 if we do nothing, resulting in more than 100 billion land animals killed annually (for a population of only 9 billion humans that could be easily fed with these plants instead). This will not only leave many more mammals and birds living in inhumane conditions, but will put pressure on fresh water supplies, contribute to deforestation, to global warming, and encourage the growth of bacteria resistant to antibiotics.

As you rightly said, allowing cruel practices, when they are not necessary and could be so easily stopped, is the worst thing we can do. The only way to stop them, is not by advocating better living conditions for factory-farmed animals, but by discouraging eating meat, poultry, cheese, fish and other animals products (yes, octopus too). It is easy for us in over-developped countries to be vegan and the more we are, the easier it will become.

I have appreciate Jones’s paper (2013) to which you refer, but there is nothing new in it: animal welfare measures have always been behind our (scientific and folk) knowledge of animal sentience and animal minds. Welfarist reforms are not a solution: not only are they not sufficiently reinforced (“for reasons of industrial expediency”, as Jones remarks), but they have been around for two centuries and, despite some success on some particular issues, they have completely failed at preventing the development of factory farms. Francione (2000, 2008) argues that these ameliorist reforms legitimate (rather than contest) the system of animal enslavement.

The welfarist ideology does not help animals because, it acknowledges that animal suffering matter, but subordinates animal interests to human interests. This goes against the principles of equal consideration of interests, claimed by most animal ethicists, like Singer and Regan (which Jones seems to cite approvingly) and against a moral principle shared by most people : we should not harm animals when it is not necessary. If we take this moral principle seriously we are lead to the strong rights-view : we should grant basic negative rights to animals not to be enslaved, harmed and killed. Eating animal products is not necessary, therefore we have to stop trying to improve the conditions of factory-farmed animals and put an end to it.

For an excellent and very short review of the arguments supporting the recognition of human rights to animals, see Donaldson and Kymlicka, Zoopolis : A Political Theory of Animal Rights, Oxford University Press, 2011 (chapter 2 : “Universal Basic Rights for Animals”).

The hardest part is to face the opposition of our friends, colleagues and family, but once we had the chance of having a glance at the psychological life of other animals and to appreciate their unique personality, it becomes so much easier to defend their most vital interests against minor human interests. No one can do that better than honest scientists who have the opportunity to encounter and work with animals and who recognize we do not need to solve the mysteries of consciousness and to solve the mind-body problem in order to appreciate the emotional lives of animals and its moral significance.

Thanks, Christiane. Here are some thoughts in reply.

I don’t think it is bad to eat the meat of an animal that has actually had a good life. What makes me continue to eat meat is not that it is merely possible that we could give farm animals a decent life, but the view that some of them do have that sort of life.

I think it’s important that most of the animals presently being eaten by humans are not animals who would have had some other, better, life in the absence of farming; they are animals who otherwise would never would have existed at all. We are responsible for their lives coming into being. We are responsible, too, for animals of those general varieties continuing to exist. Given that we control these lives, we have three options. (i) We could stop bringing them into being; (ii) we could bring them into being only if we then give them a life worth living; (iii) we could bring them into being and give them lives not worth living. I think doing the second of these is OK, as is doing the first. (It does not seem too unreasonable to me to think that (ii) is better, in fact than (i), if doing (ii) leads to the creation of more lives worth living than (i) does, but that would require a lot more argument.)

For me, the only really bad option is the third one, bringing about lives that are not worth living. And as you say, this is the reality for a great many farmed animals, probably a large majority, today. But not for all of them, I think. From my very imperfect knowledge, it seems to me that animals living free-range on farms practicing humane farming methods today do have lives worth living.

So insofar as someone manages to eat only animals who have had lives of that kind, I think there is not a problem. I don’t claim to succeed in this policy anywhere near all the time myself, however. I get lazy, or tempted by food from other sources. I might also be too willing to believe that current humane farming methods do lead to good animal lives. This reply is not an attempt to claim that my own behavior is blameless. But I think the idea that humans are bad simply because we kill lots of domestic animals is not convincing. We bring a lot of animals into being, and we kill a lot of them. The crucial question is what sort of life the animals live along the way.

Thank you for taking the time to reply!

I don’t think option (ii) is possible. Even free-ranged or so-called « humane » farmed animals end up in a slaughterhouse while the are still very young (almost babies). Here is a very simple graph comparing slaughter age and natural life span).

Most of us have no idea how much needless suffering we cause when we choose to buy animal products instead of plant-based food (even free-range, see humanemyth.org). Given that we also contribute to environmental degradation, water pollution, deforestion and to the growth of bacteria resistant to antibiotic (80% of the antibiotics in the US go to animals not to humans), I see no good reason to defend eating meat, eggs and diary products in our societies.

Thanks for the comments, Christine. I have just a few thoughts in reply.

I was asked by the editor of Biology & Philosophy to write a review of the current state of the science and biology on sentience and cognition and animal welfare. That was my charge. It was really was not the place to hash out the rights-welfarist debate. Nothing I say in that article is inconsistent with my being on either side of that debate. That’s something I do not disclose in that piece.

Further, though it is true that “animal welfare measures have always been behind our (scientific and folk) knowledge of animal sentience and animal minds” and so, in a sense, there is “nothing new” in the article, what is new is the breadth and synthesis of the data on animal sentience and cognition in one brief review article. Never to my knowledge has such a review been produced in such a brief space, including a review of welfare regulations.

Lastly, the claim that welfarist reforms harm rather than help animals is an empirical question. It is easy to look at the horrid state of animals and see welfarism as a failure. However, imagine three possible worlds. PW1 is the world where Singer and Regan never existed and no animal “rights” movement ever started. PW2 is our world. PW3 is the world where Gary Francione’s (not Singer’s) vision took hold in 1973 and abolition won the day. I agree, PW3 is the best of the three, but to claim as Francione does that PW2 is worse than PW1 is empirically dubious.

I enjoyed your article a lot. You did a wonderful job in your paper and it is indeed an excellent synthesis of the data on animal sentience/cognition and welfare regulations. I agree that PW2 is probably much better than PW1: Regan made the case for animal rights movement, he did not advocate for welfarism. The animal protection movement made some gains on some issues, but (as Kymlicka and Donaldson’s argue in Zoopolis) welfarism cannot address the problem of animal abuse, we need a political theory of animal rights. And I think the kind of work you did in your article can be very useful for that purpose.

My guess is that the red swirl is either a sponge or bryozoan colony given that it is attached to a vertical surface and it is sharing space with a bunch of other organisms that colonize calcareous rubble. It is impossible to tell though at that resolution.

Just another possibility: it might also be the eggs of a dorid nudibranch.

Yes, I just got a note also from David Scheel, a marine ecologist, who I sent a high-resolution version of the pic to. “Gastropods typically lay eggs in spiral festoons. Those look like nudibranch eggs perhaps.”

(For some nudibranchs)

Aha! I actually work in an aquarium in Santa Barbara, CA and we generally keep many species of nudibranch. They’re quite promiscuous creatures and are constantly laying eggs in our tanks, though I’ve never seen any quite as colorful as these. They’re very pretty.

I take a slightly different approach to why I don’t (more likely can’t without being queasy) eat octopus now but have no objection to others using their catch as food. I keep octopuses as pets with the expectation that I provide an environment that it smaller but less cruel than nature or a farming facility (yes, this is being done in at least one country – Mexico – and being examined by several others, they are a good source of protein but are no longer overly abundant in the wild). I also keep a dog and have kept cats. Mentally, I cannot separate pets by genus in a situation where starvation is not an issue.

Peter, as a follow to this it occurred to me that you might look at the current farming successes, failures and environments. I have had a little exposure through FIS articles (http://www.fis.com/fis/worldnews/worldnews.asp?monthyear=&day=23&id=35971&l=e&special=&ndb=1% and http://fis.com/fis/worldnews/worldnews.asp?l=e&id=45160&ndb=1 )but would love to find/read more about the process. Admittedly, my interest is selfish and directed toward hobbyist keeping, seeing a positive side to learning more about raising them in captivity or using captive raised for the home aquarist but the topic is interesting on several levels. Conservation being one in that, numbers are declining but statistics are not readily available. Reading old pamphlet essays mentioning quantities caught daily in pots justifies acknowledging decline but there is no current concern about extinction for most. There is, of course, a whole can of worms that can be opened in this direction.

Seems to me that octopuses can be quite happy in captivity. (Here my information is second-hand, as I’ve not had one.) When octos are stressed, it shows, so a watchful human keeper would know if there was a problem. From many accounts (including yours) octos find domestic life interesting.

This I reckon is a situation where the details of the animal’s temperament matter a great deal. I can’t understand why people want to keep dogs in Manhattan locked in tiny apartments, alone much of the day, when all a dog wants to do is be around its companions (human or canine) and to roam around. They should keep octopuses instead.