One of the most unusual scientific works about cephalopods is a monograph – published in a journal, but the size of a small book – that came out in 1982. It was called: “The behavior and natural history of the Caribbean Reef Squid Sepioteuthis sepioidea. With a consideration of social, signal, and defensive patterns for difficult and dangerous environments.” The authors were Martin Moynihan and Arcadio Rodaniche, two biologists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, Central America.

The monograph was controversial for its final chapter, which is about communication. Moynihan and Rodaniche argued that squid have a simple form of language, a language of skin patterns and arm displays. This was an adventurous interpretation of cephalopod communication.

The monograph was controversial for its final chapter, which is about communication. Moynihan and Rodaniche argued that squid have a simple form of language, a language of skin patterns and arm displays. This was an adventurous interpretation of cephalopod communication.

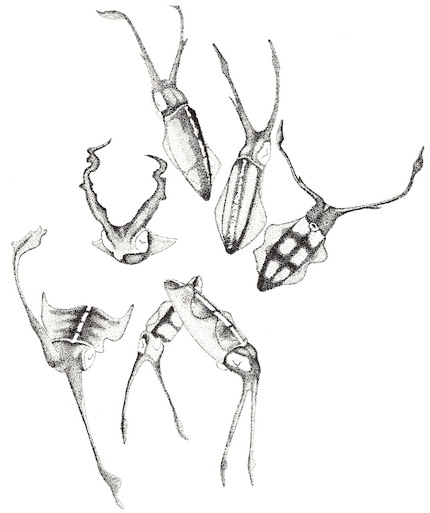

Moynihan and Rodaniche compiled a catalog of the signals their squid seemed to be sending (a plate is here) and looked especially at combinations of signals – colors plus patterns, patterns plus body shapes: “the Fin Stripes and the Belly Stripe may be roughly comparable to adjectives or adverbs….” Their paper is unusual also for its style; it is dense with careful observations, but written with a kind of affection, and occasional emotional engagement with the lives of these complicated, often anxious animals.

The topic of this post is not signals, though. In a chapter that compared the Panama squid to other cephalopods, Moynihan and Rodaniche briefly described an octopus. They called it the “Larger Pacific Striped Octopus,” a species that had not been studied, with no official name. They said they had come across a “colony of 30-40 individuals,” with some octopuses sharing dens. Octopuses were generally believed to be very solitary in their habits, and nothing like this had been seen before.

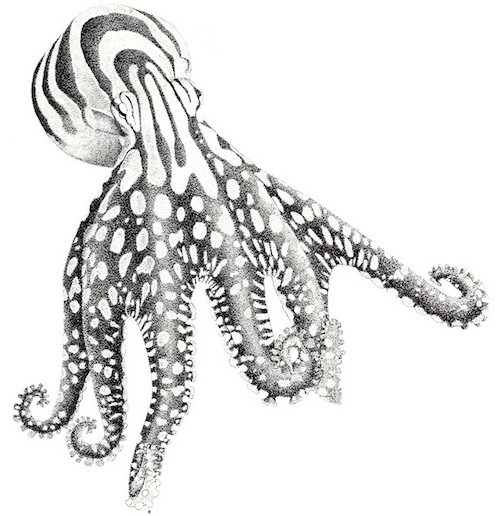

Arcadio Rodaniche became, during his scientific career, an accomplished artist. Now retired, he has an artistic website here. For the 1982 monograph he drew the beautiful drawing of the mysterious Larger Pacific Striped Octopus which I reproduced above, scanned from the original article. Here is another drawing from the monograph, of displays in their reef squid.

In 1991 Rodaniche published an abstract of a paper describing the striped octopus in more detail. Intrigued by the 1982 description, a few years ago I tried to track down the article, but all I could find was the abstract. And there was no sign of the Larger Pacific Striped Octopus.

No sign until 10 days ago, when Roy Caldwell and Richard Ross of UC Berkeley and the Steinhart Aquarium sent out a press release, posted on the TONMO website. The lost octopus has been found, and for the last year or so Caldwell and Ross have been raising them in the lab. They released pictures and a video (below). The octopus looks just like Rodaniche’s old drawing.

At the moment all we have is the press release with some lab observations. But Ross and Caldwell confirm that these octopuses are gregarious. They are also iteroparous – females do not die after hatching a single brood of eggs, as in other octopuses, but can lay several broods. And they mate “beak to beak,” unlike any other known octopus.

There is also something to think about here regarding skepticism and peer review:

According to Caldwell, Rodaniche’s descriptions of the behavior of this species were so outside the norm of what biologists at the time thought octopuses did, they were dismissed by other cephalopod biologists. Unable to pass peer review, the manuscript was never published and the animal was forgotten. Living LPSOs weren’t seen again until they were rediscovered last year.

What is the relation between these behaviors and those seen at Octopolis, a site in Australia I have written about here where another species of octopus, Octopus tetricus, lives at close quarters? I’ve never seen a beak-to-beak mating in the Australian species. I have seen pairs occupy the same den (in a Sydney location).

And here is the most intimate association I’ve seen in this species, down at Octopolis:

These ones are not mating in this shot, though they did mate later.

Compare the beak-to-beak matings in the Larger Pacific Striped Octopus; this is from the press release, a photo taken by Richard Ross:

Below, lastly, is the video posted by Ross and Caldwell in their press release. As the photo above and the video show, the lost octopus is also a remarkable looking animal. On the TONMO site there is speculation about whether, given the flamboyant appearance, this may be another octopus harboring serious venom. No one knows yet.

________

The reference for the 1982 monograph by Moynihan and Rodaniche is Advances in Ethology 59, (S25), pp. 5–150. The drawings above are details of figures in this publication.

Someone from marketing give a hand to this species! I’m thinking about how the African wild dog was rebranded as African painted dog. “Lost octopus” is a good start. Maybe something to emphasize their unusual sociality. Kibbutz Octopus? Or just name it after Stephen Colbert: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aptostichus_stephencolberti

Is it possible to get cameras inside the dens of co-habitational octopi to see what they get up to? David Attenborough style! Maybe you could build a really awesome octopus penthouse with a camera in it and good lighting — then see if anyone moves in. I would love to know how they are looking at each other when they are involved in these displays. Does the recipient octopus position itself for a good vantage point? Does the displaying octopus check the recipient octopus to see if the display is going over well? Or would you rather go with a hard-core skin-sensing hypothesis and say the eyes can be totally closed and each octopus’ skin can sense and respond to the others’ locally without need for the central nervous system? Maybe that would be the easiest test of the colorblind camouflage hypothesis — not requiring any fancy investigations of photopigment variants — blindfold them or glue their eyes shut temporarily (humanely) and then see what kind of camouflage they get up to (if any).

Pingback: » Larger Pacific Octopus coverage: SFChronicle, GiantCuttlefishSF Gate, Sci-News, Reef Builders, Advanced Aquarist Packed Head

Non aggressive beak to beak (or perhaps more likely most sensitive sucker to most sensitive sucker) is interesting. It makes you wonder is kissing or sensitive touching is evolutionary in pairing or at least showing an interest in mating.

Yes, and imagine what sucker-to-sucker contact would feel like, given all the sensors that an octopus has in each sucker. (Though there is also the issue of which sucker-derived information gets all the way to the octopus’ brain.)

We know that there is some chemical sensing with the suckers but I wonder if there is transmission as well. I’m thinking something along the caption lines of, “mmm, you smell good lets … dance”. If there is a transmission, I wonder if only some species use it or if there is sucker contact further down the arms that we have not picked up on.

Alternately, could there be a calming, drug affect that keeps the female from attacking the male. The later less likely I think since they are not devouring each other in their living arrangements.