23. Eat?

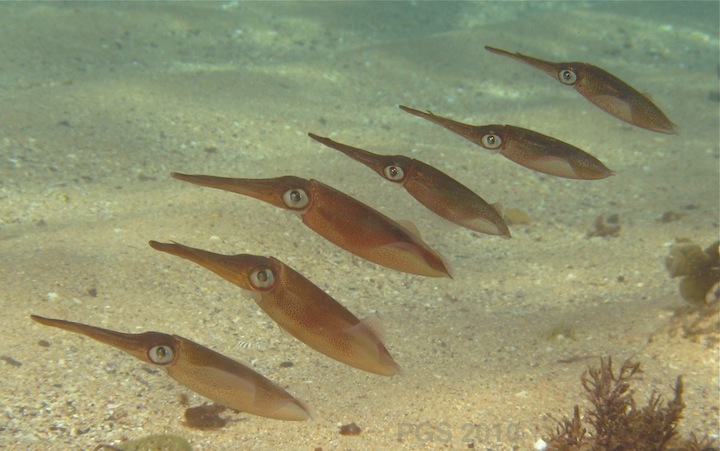

There they are on the menu – grilled octopus, calamari, squid ink linguine. Is it OK to eat cephalopods? Or are these animals too smart for us to kill and consume them just because they taste good?

I have stopped eating them, especially octopuses. But I think of this as a decision made for sentimental reasons, not for reasons of principle. This is because I still eat various other kinds of meat, though I avoid (imperfectly) the products of cruel factory-farming. The octopuses that end up on menus are short-lived and wild-caught animals, and do not come from endangered species. Anyone who eats bacon or salami is eating an animal that was kept in captivity and killed for food despite having high intelligence and an undeniable capacity to suffer. In the case of factory-farmed pigs living in close confinement, their treatment is terrible and the suffering must be very great. But even with humanely farmed animals, it is hard to see how eating steak could be justifiable while eating octopuses was not. As I still eat steak, I can’t claim that my avoidance of octopuses is based on a principle that is being consistently applied. So I think of it as a largely sentimental choice; I just don’t want to eat them any more.

Now the ethical issue is on the table, though, what kinds of “smartness” are morally relevant? Which features of an animal’s intelligence and lifestyle are the ones that matter to a decision like this?

The capacity to suffer is an obviously relevant feature, one that philosophers like Peter Singer have focused attention on for many years. For a while discussions in this area were often based on a common-sense picture of which behaviors indicate a capacity to feel pain. Two lines of work are presently going deeper. First, there is impressive physiological work on which animals feel pain. Other work tries answer these questions: once we agree that physical pain is bad, which features of an animal make it able to experience more complicated forms of suffering, in the way humans can? Which animals can experience fear that goes beyond immediate physical threats? Which ones form relationships, or plans, that magnify the ways in which life can go well or badly for them?

In the case of octopuses we are a long way from giving good answers to most of that second set of questions. The existence of stress can be pretty clear in octopuses, and that is one important form of suffering that goes beyond immediate physical injury. As we learn more about the complicated way they engage with the world, some of these findings may end up being morally relevant. An example of what I called “the complicated way they engage with the world” is the fact that some octopuses recognize and react differently to individual human keepers when they are in captivity. Anecdotes of this kind came out of labs and aquariums for years, often because an octopus took an apparent dislike to a keeper, sometimes the one whose job it was to clean the tank. This keeper would be drenched with water whenever they came nearby. So far this is just anecdote. But in 2010 Roland Anderson and his co-workers tested this more rigorously with an experiment on the Giant Pacific Octopus. To avoid making the task too easy, the different humans working with the octopuses wore the same clothes. The octopuses did, after a few weeks, distinguish pretty clearly between a human who fed and a human who slightly irritated them. (I am not sure from the paper how much individual variation there was – whether all octopuses did this or just some of them.)

The welfare of octopuses in research has become a contentious topic. When I first read some of the classic papers about octopus brains and behavior from the 1970s, I was shocked at how brutal the treatment often was. Things have changed, fortunately. In 1986 the United Kingdom set a level of protection in experiments that was applied to all vertebrate animals plus a single species of octopus, Octopus vulgaris. Then in 2010 the European Union laid down quite strict protections for all cephalopods, because of “scientific evidence of their ability to experience pain, suffering, distress and lasting harm.” I have heard some criticism of this new rule, especially because of the paperwork burden it will create. Although few things drive me madder than administrative paperwork, I am glad to see this step.

Given all this, why don’t I just become a vegetarian?

Perhaps I should, and I admire vegetarians. I have no problem with carnivory in itself, though, or with keeping animals for food. The problems are with how it’s done. Farmed animals can be given a life worth living, ending in a quick and low-stress death. Some animals through the history of domestication and farming have been given a life like this, and others have not. Most current farming is probably far from this standard. It would be better not to live at all than to live as a factory-farmed mammal. In the US, high-density farming of cattle and pigs seems especially bad. In Australia, the “live export” of sheep and cattle in suffocatingly hot container ships to countries in the Middle East and Asia where they are slaughtered in brutal ways is sickening – allowing this, when it could be so easily stopped, is the worst thing the country currently does. I don’t think it would be so difficult to give all farmed animals – animals whose existence we are entirely responsible for – a life worth living. To the extent that we can’t or won’t do this, we should stop bringing those lives into being.

_____________

Notes

A new survey article by Robert Jones about animal welfare and sentience is here. A book about all these issues by someone who knows them much better than I do, Lori Gruen, is here.

A 2008 report on factory farming in the US, by the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, looking at public health and economics as well as animal welfare, is here. From the report: “The present system of producing food animals in the United States is not sustainable and presents an unacceptable level of risk to public health and damage to the environment, as well as unnecessary harm to the animals we raise for food.”

The octopus-plus-camera-lens photo was taken with Matt Lawrence at Octopolis.

Does anyone know what the decorative red swirl is on the second photo above, the one where an octopus is presenting a scallop shell like a shield?